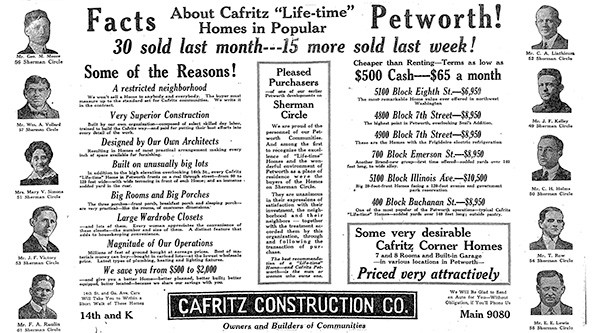

Commercial for Cafritz houses within the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC. (The Washington Submit, January 10, 1926)

In early 1926, Cafritz Development positioned an commercial in The Washington Submit celebrating the pace with which their “Life-time Houses” have been promoting within the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC. Common readers of the newspaper have been seemingly already acquainted with the event because of information articles that praised Morris Cafritz’s “imaginative and prescient and braveness” and a relentless stream of ads bringing his over 3,000 new models to market. 4 years prior, Cafritz had bought an over 38-block plot of land in a beforehand wooded a part of city and promised to regrade the hilly panorama, pave roadways, and construct homes at costs reasonably priced to DC residents of reasonable means.

This explicit commercial included a listing of the explanation why Cafritz houses have been so standard. Maybe potential consumers can be swayed by the “superior development” or the “unusually huge heaps.” Perhaps it was the “giant wardrobe closets” or the promise that one can be “cheaper than renting.” Then once more, perhaps it was the sign that Cafritz’s Petworth houses have been for white consumers solely. If the photographs of 10 white “happy purchasers” didn’t make that clear, then the promise of a “restricted neighborhood—We gained’t promote a Residence to anyone and all people” definitely did.

Whether or not or not Cafritz held prejudiced views, he acknowledged the financial usefulness of restrictive covenants and benefited from a authorized setting that inspired discrimination and segregation in housing. By prohibiting any future sale of the property to Black or different non-white house owners, restrictive covenants gave white consumers confidence that their houses and neighborhoods would stay white enclaves and due to this fact retain the “enduring worth” that Cafritz promised for his “lifetime houses.” And it labored. By 1948 Cafritz had amassed such wealth from actual property growth that he included a basis bearing his and his spouse’s title.

Right this moment, the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Basis focuses its grantmaking within the metropolis and area the place Morris constructed his wealth and the place gentrification—in Petworth and elsewhere—continues to displace Black households at disproportionate charges. It is usually certainly one of a number of DC-area foundations profiled in a brand new report from the Nationwide Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) on “Philanthropy’s Position in Reparations for Black Folks.” The report (I served on the advisory committee that produced the report) makes the case—hardly distinctive to the Cafritz Basis or to the DC space—that racialized hurt is the supply of capital behind up to date giving and considers what’s owed to individuals harmed within the creation of endowments. One takeaway: Conventional practices of grantmaking are inadequate.

Are you having fun with this text? Learn extra like this, plus SSIR’s full archive of content material, whenever you subscribe.

What does it imply to reckon—actually and brazenly—with the supply of philanthropic wealth? Doing so means contemplating the connection between philanthropy and racial capitalism and acknowledging that classes of race are constituted and constitutive of capitalism and the creation of wealth. It additionally means participating in historic analysis and accepting what historic proof can and can’t reveal. Lastly, it means linking racialized harms prior to now with efforts at redress and restore within the current.

Philanthropy is beginning to discuss extra about reparations. The conversations stay small and overdue, however latest momentum is notable with new organizations, publications, assets, and frameworks exploring how philanthropy can—and, within the eyes of many, ought to—interact the motion for reparations in america.

A subset of funders have began to shift assets into the arms of advocates

calling upon the federal government to bear a technique of redress and restore. This transfer acknowledges the federal authorities as, within the phrases of students William A. Darity and Kirsten Mullen, “the succesful and culpable social gathering” that set and enforced insurance policies and legal guidelines to actively construct the property of white households and destroy the property of Black households.

One other method to consider philanthropy and reparations—which isn’t mutually unique from the funding the advocacy for presidency reparations—is to think about whether or not foundations are additionally “succesful and culpable.” In eras of each slavery and freedom, the accrual of wealth in america can’t be separated from legacies of extraction, violence, and denial of Black individuals and different minoritized teams. That is still true even when that wealth was donated to advertise a public good.

Universities are beginning to confront their legacies and ties to slavery. Georgetown College, for instance, gained consideration following the disclosure that the college owned after which bought 272 enslaved males, ladies, and kids in 1838 to fund the college’s operations. Pressured, particularly, by scholar teams, Georgetown has created scholarship alternatives for descendants of the “GU272,” amongst different acts of reconciliation and restore. Now over 100 establishments of upper training have joined the Universities Learning Slavery Initiative

with a dedication to researching and reflecting on their ties to human bondage and racism.

Foundations may comply with this mannequin. Admittedly, there are key distinctions between universities and foundations that make such a transfer unlikely and troublesome. Philanthropic leaders are apt to focus on how few philanthropic endowments have such direct ties to enslavement for the reason that authorized infrastructure that creates and regulates foundations first emerged within the twentieth century. They may additionally level to an absence of proof of hurt as apparent as a invoice of sale for human beings. Moreover, with out constituents like college students to push for institutional acknowledgement or archivists and school to guide the analysis, foundations are extra insulated from expectations of transparency and challenged to seek out and look at the historic file. Nonetheless, the uncomfortable work of researching, reflecting, and reckoning with the previous stays crucial—and is feasible. Sources do exist—typically within the public area—that help a case for philanthropic restore and redress.

Analysis into the origins of endowments means scouting, analyzing, and utilizing proof in ways in which require each creativity—pondering expansively about the place proof would possibly exist—and precision. The primary, apparent place to look are within the archival information of foundations and the non-public papers of their founding donors. But, the enterprise practices that generated that wealth could or will not be included in such collections, which is perhaps housed in a public archive or stored non-public. Native historical past facilities, newspapers, oral historical past collections, and different repositories would possibly maintain information that element “from beneath” how sure practices benefitted some and harmed others on the premise of race.

Contemplate once more Morris Cafritz. Cafritz’s use of restrictive covenants is sort of evident from a search of his ads in The Washington Submit. Such language was typically thinly coded, with references to Petworth as a “refined and unique neighborhood,” with “precautions to maintain out undesirables,” and “favorable restrictions for the safety of house house owners.” Different ads touted a “restricted neighborhood” the place “We write it within the contract.” One commercial celebrated 23 Cafritz homes bought in 15 days “in the perfect restricted residential part” of town. Each open and veiled dialogue of covenants suggests they have been seen as fascinating to white customers.

Historic analysis, regardless of how fruitful, raises new questions whereas answering others. When that occurs, the aim is to contextualize what direct proof is out there in more and more broad concentric circles. To grasp Morris Cafritz’s actions required studying on the historical past of Washington DC, on the historical past of actual property growth, and on race and public coverage. Crucial questions embody: What have been the circumstances that enabled the founding donor to amass such wealth? And, how did these circumstances favor some over others? In fact, contextualizing the actions of rich people within the authorized and financial panorama of their time doesn’t absolve them of collaborating in methods of hurt and denial.

An early Cafritz-built home in Washington, DC, c. 1916-1917. (Library of Congress, Prints & Images Division, Nationwide Photograph Firm Assortment)

Earlier than 1948, restrictive covenants on property deeds usually prohibited the sale of the property to Black or different non-white consumers. Such clauses have been challenged repeatedly in court docket however upheld on the grounds that the court docket had no authority over non-public transactions between people. (Coincidentally or not, Cafritz included his basis the identical yr that Shelley v. Kraemer struck down the enforcement of restrictive covenants.) Analysis in public information by native organizations similar to Prologue DC additional confirms the frequent use of those exclusionary mechanisms in Washington D.C.

This was not racism of the person or interpersonal selection, although that definitely existed on the time and since. Fairly, these practices mirrored an evaluation of housing values that believed the presence of Black individuals lowered the values of particular person properties and neighborhoods. The connection between race and worth was a core tenet of actual property even earlier than the notorious Residence House owners Mortgage Company maps graded and “redlined” particular person neighborhoods. It was taught in economics textbooks and enshrined in 1924 within the code of ethics for the Nationwide Affiliation of Actual Property Boards that prohibited brokers from integrating neighborhoods by “introducing” members of a race or nationality not already current.

Analysis findings can even current surprises. Categorised ads in The Washington Submit

reveal that Cafritz additionally rented and bought properties to Black households—he simply did so inside present patterns of segregation, advertising and marketing models as “for coloured” occupants. It was worthwhile to take action. As historian N.D.B. Connolly has written, “Racially dividing actual property generated wealth as a result of it restricted the mobility of customers, thereby confining demand, manufacturing shortage, and driving up costs on each side of the colour line.” That Morris may interact in such practices whereas additionally being charitable together with his donations and serving in later years on the board of the United Negro Faculty Fund is hardly a contradiction. As with every historic narrative, the truth was difficult and reflective of the workings of racial capitalism that eliminated private animus or prejudice and as an alternative structurally baked such preferences into the regulation, coverage, and market.

Discrimination, racism, and segregation have been key components of Cafritz’s enterprise technique and resultant fortune that endowed his household’s basis. There will not be a named plaintiff who was denied a house in Petworth and subsequently missed a possibility to construct wealth and fairness in a “lifetime” house. However we all know that such individuals existed whether or not or not we all know their names, and we are able to take into account how Cafritz’s use of covenants helped white households develop their property (and his personal), whereas denying the identical alternative to Black households. His boasting of covenants within the press, in addition to his participation in skilled and monetary associations, additionally helped deepen and legitimize the affiliation between race and actual property worth within the D.C. area and past.

Whether or not the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Basis owes one thing right this moment for actions prior to now shouldn’t be for me to say. I’m neither an knowledgeable on reparations nor somebody harmed by what Cafritz did and due to this fact mustn’t essentially have a job in designing what restore would appear like or what form redress ought to take. I’m, nonetheless, a historian whose skilled expertise embody the sorts of analysis crucial to tell how foundations go about acknowledging and understanding their previous.

For a area like philanthropy that has been closely influenced by economics and is keen to quantify and measure affect, the notion of dealing with fragmentary proof could also be unsettling. It’s, nonetheless, a every day actuality for historians whose skilled skillsets embody contextualizing what proof does exist in bigger patterns and processes. Even fragmentary historic proof can reveal essential, if painful, truths. What is required in philanthropy, then, is a unique—and extra capacious—understanding of what “proof” of hurt seems like and, maybe, an acceptance of certainty and uncertainty co-existing.

If historic analysis is one a part of my job as a college professor, instructing is one other. Once we talk about racism in my lessons, my college students take into account a metaphor provided by psychologist and scholar Beverly Tatum. In her guide Why Are All of the Black Children Sitting Collectively within the Cafeteria? And Different Conversations about Race, she likens white supremacy and racism to “smog within the air….day in and time out, we’re respiratory it in.” She continues to say that we could or will not be at fault for creating the air pollution, “however we have to take duty, together with others, for cleansing it up.” My college students discover this metaphor helps shift emotions of guilt, denial, disgrace, or resentment into motion. I supply the identical steering to philanthropic leaders.

Present boards of trustees could not have created the racial wealth hole that’s so urgent right this moment. Nor, for that matter, have been founding donors similar to Morris Cafritz the one polluters. The purpose is to not disgrace or vilify; it’s to acknowledge that we within the current maintain a duty for the clean-up by interrupting cycles set in movement by others and which we could or will not be perpetuating. Foundations have the assets with which to take action.

As NCRP’s report on reckoning argues, “A reparations strategy is a pure step for wealth-holding charitable organizations… [whose] mission is geared toward bettering the well-being of individuals and communities.” That may entail rethinking how they function, the place they fund, what priorities they set, and who sits on the board. It would even imply conceiving of philanthropy in another way: following fashions, maybe, from the “land again” motion slightly than fashions of charity or funding.

Foundations are unaccustomed to pushback given how the facility hierarchies inherent in grantmaking substitute criticism with gratitude and reward. Altering the norms of the sphere to debate brazenly, transparently, and reflectively the supply of the endowed wealth won’t come simply nor comfortably and can take sustained help from each inside foundations and with out. Nonetheless, philanthropic entities have a possibility—maybe an obligation—to have an open dialog about racial capitalism in america and their relationship to it. That may be a real instance of the management and social change that these entities so try to attain and a real success of their mandate to serve the general public good.

Assist SSIR’s protection of cross-sector options to international challenges.

Assist us additional the attain of modern concepts. Donate right this moment.

Learn extra tales by Claire Dunning.