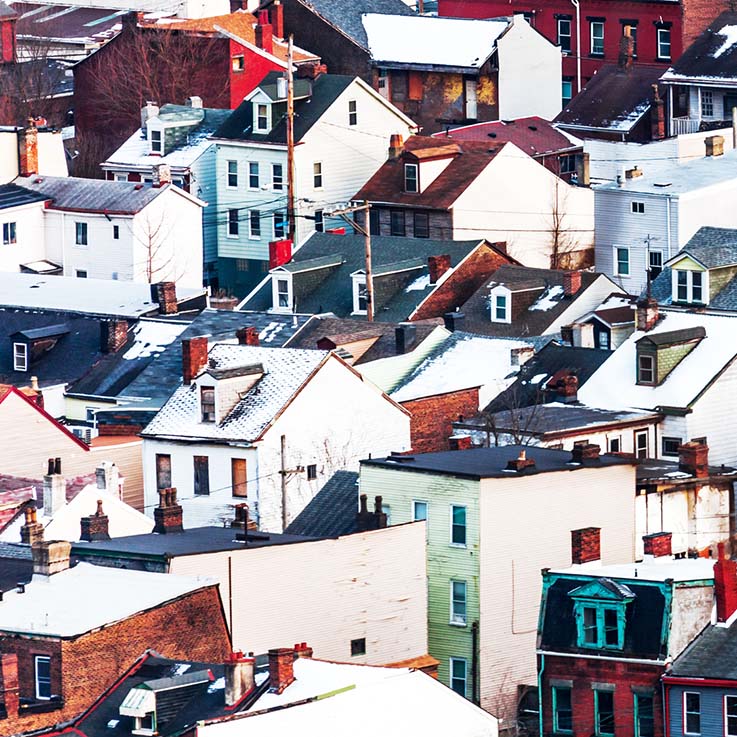

(Photo by iStock/peeterv)

For many families, owning a home is not only a source of pride but also the foundation of financial stability and opportunity that can be passed down through generations. Unfortunately, discriminatory systems and predatory actors often prevent heirs from maintaining and building upon these hard-fought gains. This loss can devastate families and disproportionately holds Black and Brown families back from financial growth over generations. It may also help explain why the homeownership gap between Black and white Americans has barely changed at all since 1960.

Philanthropy has long prioritized programs to increase new homeownership, but this is only part of the equation. To help families build wealth and protect hard-fought gains over generations, funders should also prioritize homeownership preservation. Maintaining and passing down property as an asset to loved ones is an important aspect of intergenerational wealth. Among the challenges to homeownership preservation efforts, however, is a complicated legal landmine known as “tangled titles,” commonly referred to as “heirs’ property.” Tangled titles disproportionately affect Black and Brown families due to inequitable access to legal services and persistent discrimination that has broken many families’ trust in the systems governing property ownership.

Fortunately, tangled titles are a preventable problem—and one that philanthropy can and should play a meaningful role in solving.

Tangled titles arise when a property owner passes their home or land down to multiple heirs without a clear title. Most often, this occurs when a parent dies without a will and their home goes automatically to multiple children. This ambiguity creates a challenging legal situation where all the children must unanimously decide on matters relating to the property. If one wants to sell the property, but the others don’t agree, the property cannot be sold.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR’s full archive of content, when you subscribe.

This makes it easy for predatory developers to buy one of the shares from an heir—say, a sibling who wants to sell the property—and then use their influence to force the sale of the entire property so that it can be developed. Without being able to prove ownership via a clear title, then, heirs can lose their home. According to the National Consumer Law Center, “heirs’ property” owners may also struggle to obtain homeowners insurance and property tax relief credits, receive home repair grants and loans, or take out home equity lines of credit. Ultimately, these factors also put homeowners with tangled titles at a greater risk of losing their property, resulting in familial displacement and lost intergenerational wealth.

A problem this widespread requires multifaceted solutions. Funders must target various actors in the homeownership continuum, including some that may require new ways of working for philanthropy, such as lenders, insurance companies, state and federal housing and tax agencies, estate planning lawyers, community development financial institutions, and housing counselors.

Funders should confront this problem in three primary ways.

First, while some resources are already being dedicated to research, funding new research that drives policy change is a valuable place for philanthropy to start. Efforts from organizations like the National Consumer Law Center, Urban Institute, and Housing Assistance Council, combined with insights and analysis from industry thought leaders, are driving more awareness of tangled titles and putting necessary pressure on policymakers to consider new solutions. These decades of research are starting to bear fruit in the form of policies like the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, a model state law first passed in 2011, which includes more protections for homeowners and has been enacted in 22 states so far.

Second, philanthropy should push the existing market to provide financial products for families to help resolve these issues. Because each circumstance and community need is different, community development financial institutions (CDFIs) are often the strongest partners for funders to work with on the ground. CDFIs act as the economic engines for smaller communities and are already positioned to gather various local actors and tackle issues holistically. By investing in CDFIs, funders can raise local awareness and fund home preservation solutions that work for each individual community.

Finally, philanthropy should expand access to affordable and representative legal services that could help resolve tangled titles or prevent them entirely through proper estate planning. There are not enough pro-bono or low-cost legal services to meet the need—let alone enough lawyers in the industry who come from the same diverse backgrounds as the people they represent. To help move the needle, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and JPMorgan Chase and Co. are funding a legal clinic at Howard University School of Law designed to help Black and Brown families and families with low incomes deal with heirs’ property, while educating the next generation of attorneys. Other funders should take up similar initiatives.

To ensure everyone in the United States can live their healthiest life possible, capital must flow equitably to families of color and those with low incomes, who continue to face disinvestment from the agencies and systems that should be helping them. By investing in homeownership preservation, funders can help foster healthier, more prosperous communities and close the racial wealth gap once and for all.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Ruth Gao.